Introduction

In a blog post a few months ago, I announced that my team had released the new “global” IBM Cloud Console (formerly Bluemix Console) allowing all public regions of the IBM Cloud platform to be managed from a single location: https://console.bluemix.net. This took us from four addresses (one for each of the four public IBM Cloud regions at the time) to a single geo load-balanced address. Users would now always get the UI served from the geographically closest (and healthy) deployment, resulting in improved performance and enabling failover to greatly increase availability. In this post, I’ll dig a bit deeper so that you can gain insight into what it would take for you to build similar solutions with your own IBM Cloud apps. In particular, I’ll discuss:

- High-level features of our architecture and the enabling third-party products we used

- Things to think about while building a health check to determine when failover should occur

- Considerations for coding apps so they are enabled to run in multiple data centers

- Using the architecture to smooth the transition to new technology

Hybrid Architecture With Akamai and Dyn

The IBM Cloud Console has long been fronted by two offerings from Akamai:

- Akamai Kona for web application firewall (WAF) and distributed denial of service (DDoS) protection.

- Akamai Ion for serving static resources via a content delivery network (CDN), finding optimal network routes, reusing SSL connections, etc.

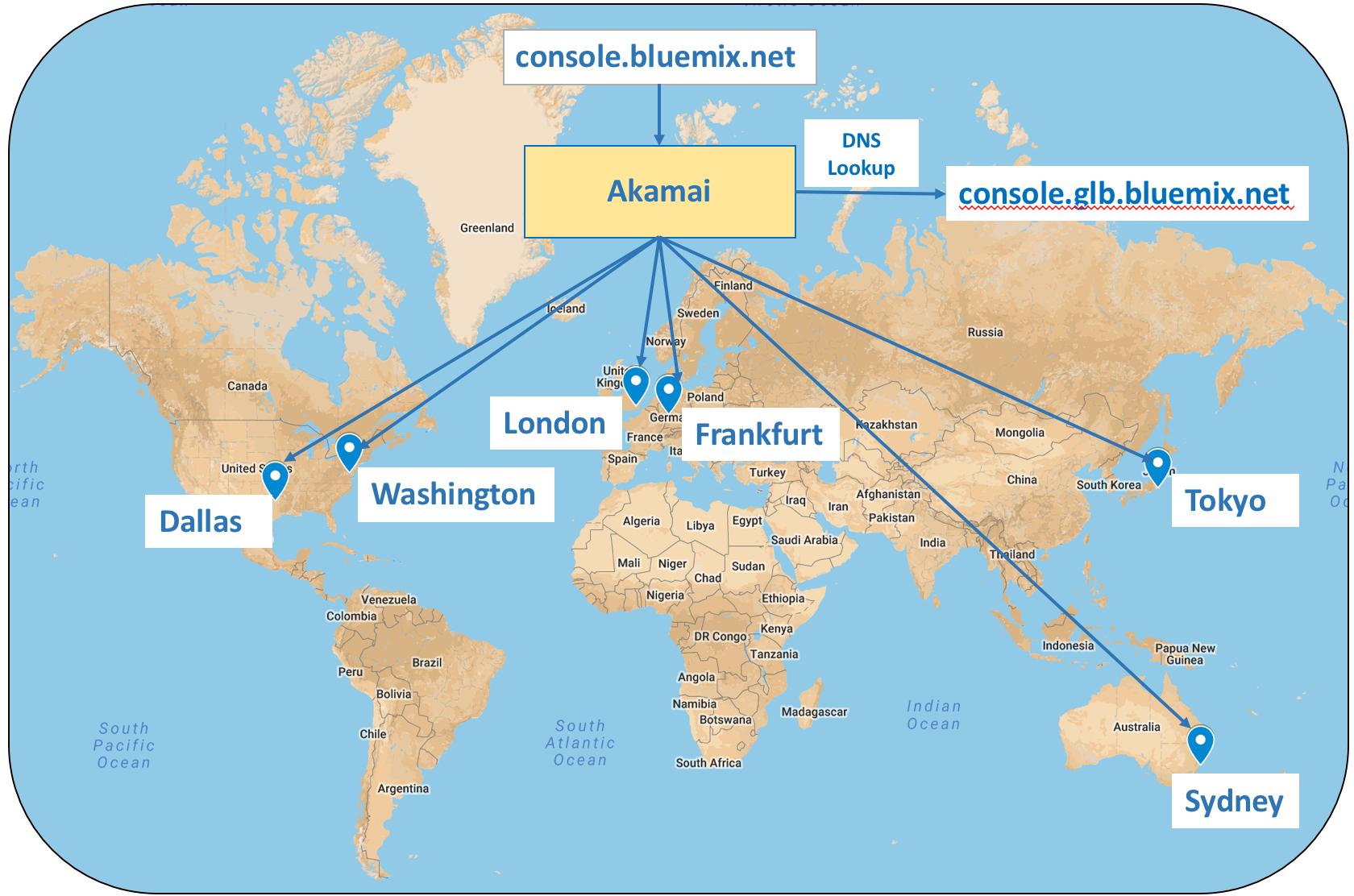

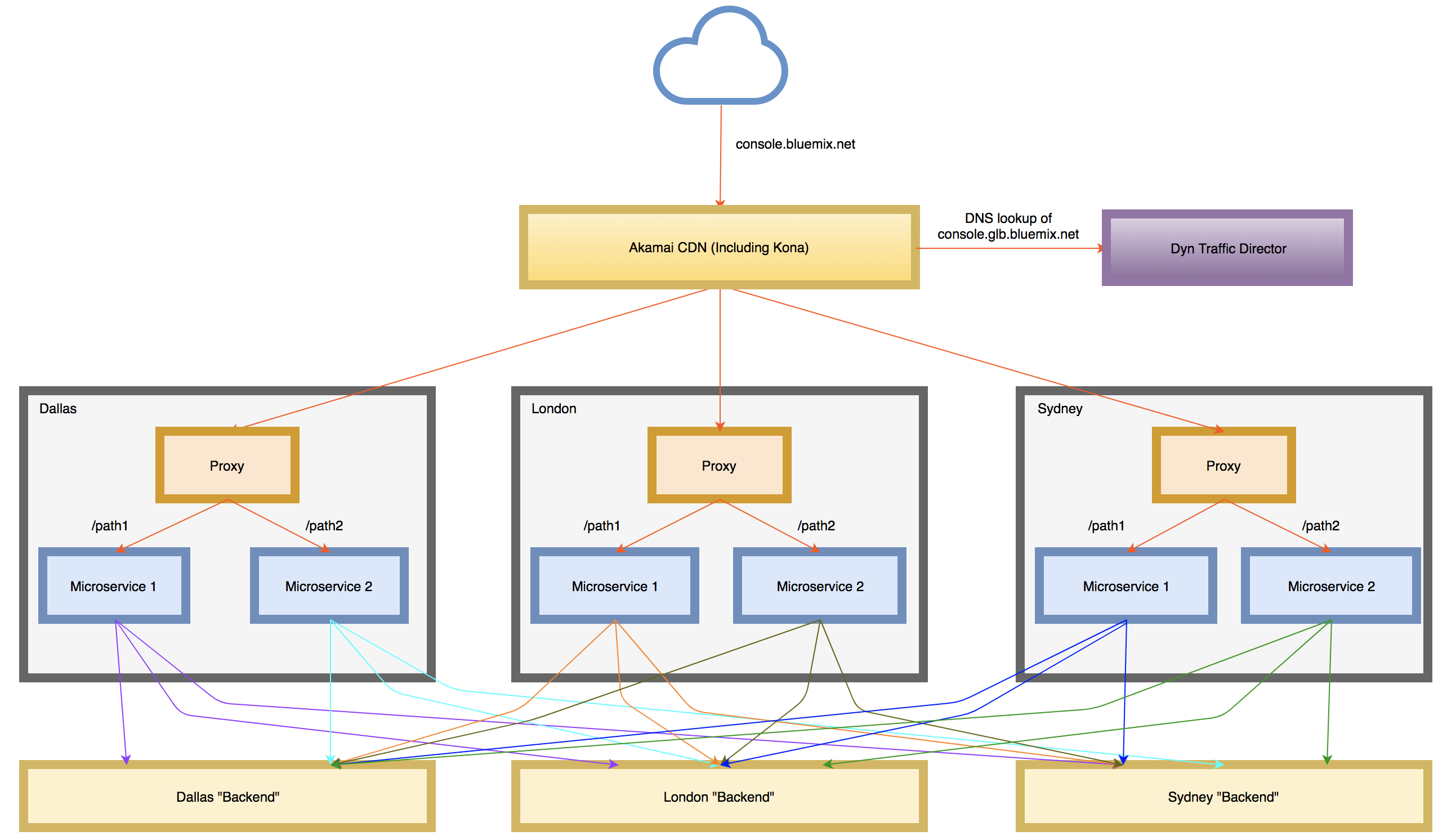

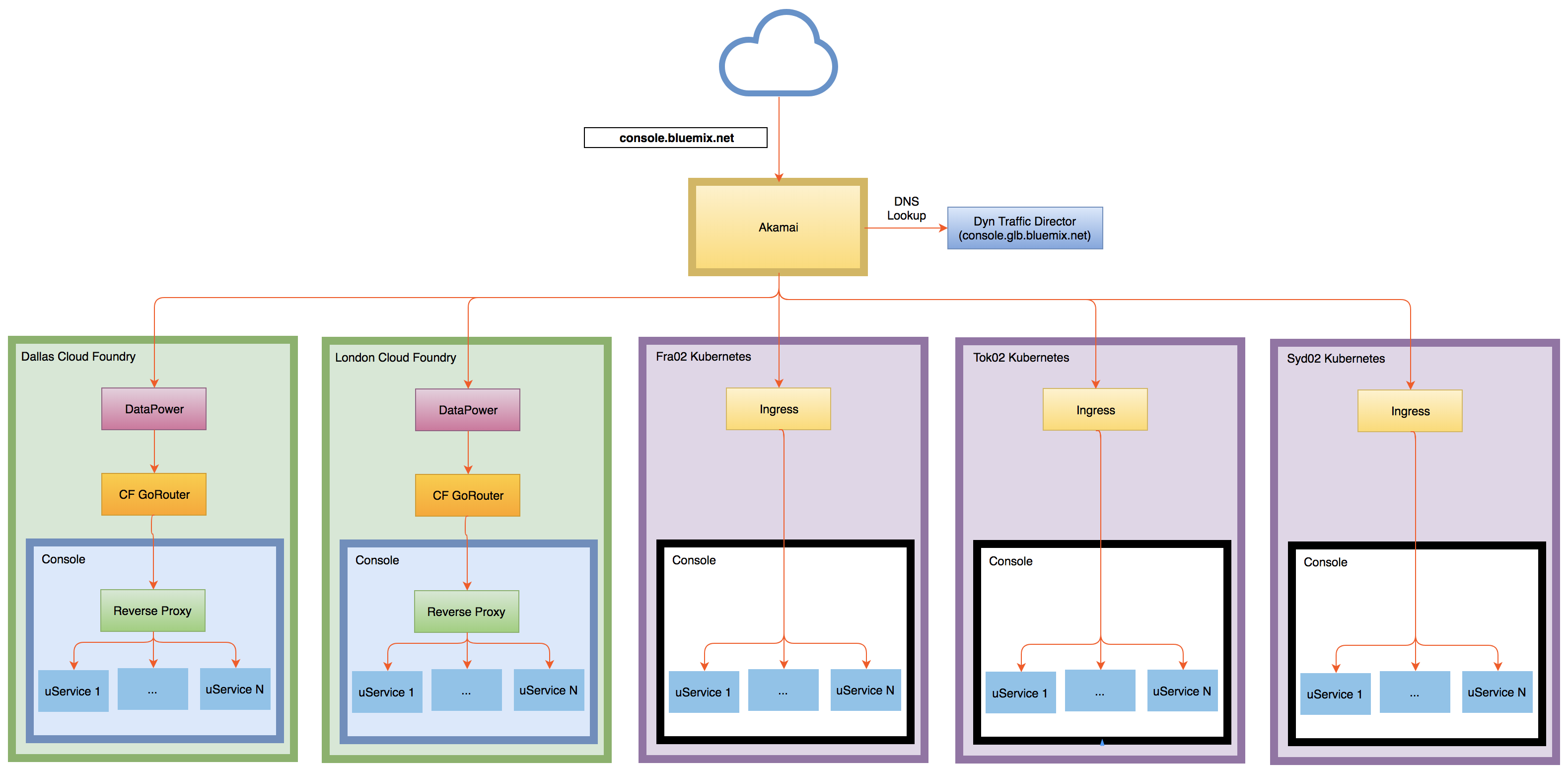

With the implementation of the global console, we added the Dyn Traffic Director (TD) product to the mix. All requests to console.bluemix.net are sent to the Akamai network, and then Akamai acts as a proxy. Akamai does a DNS lookup to determine the IP address to forward the request to by using a host name which has been configured using a Dyn TD. The Dyn configuration is setup to spread traffic based on geo location to one of six IBM Cloud data centers. This is shown in the diagram below.

Since Akamai also offers its Global Traffic Management (GTM) product for load balancing, it may seem a bit strange to be using this hybrid solution. But, we had a an existing contract with Dyn, and we simply decided to leverage that instead of adding GTM to our Akamai contract. This has worked quite well for us.

Importance of Health Check

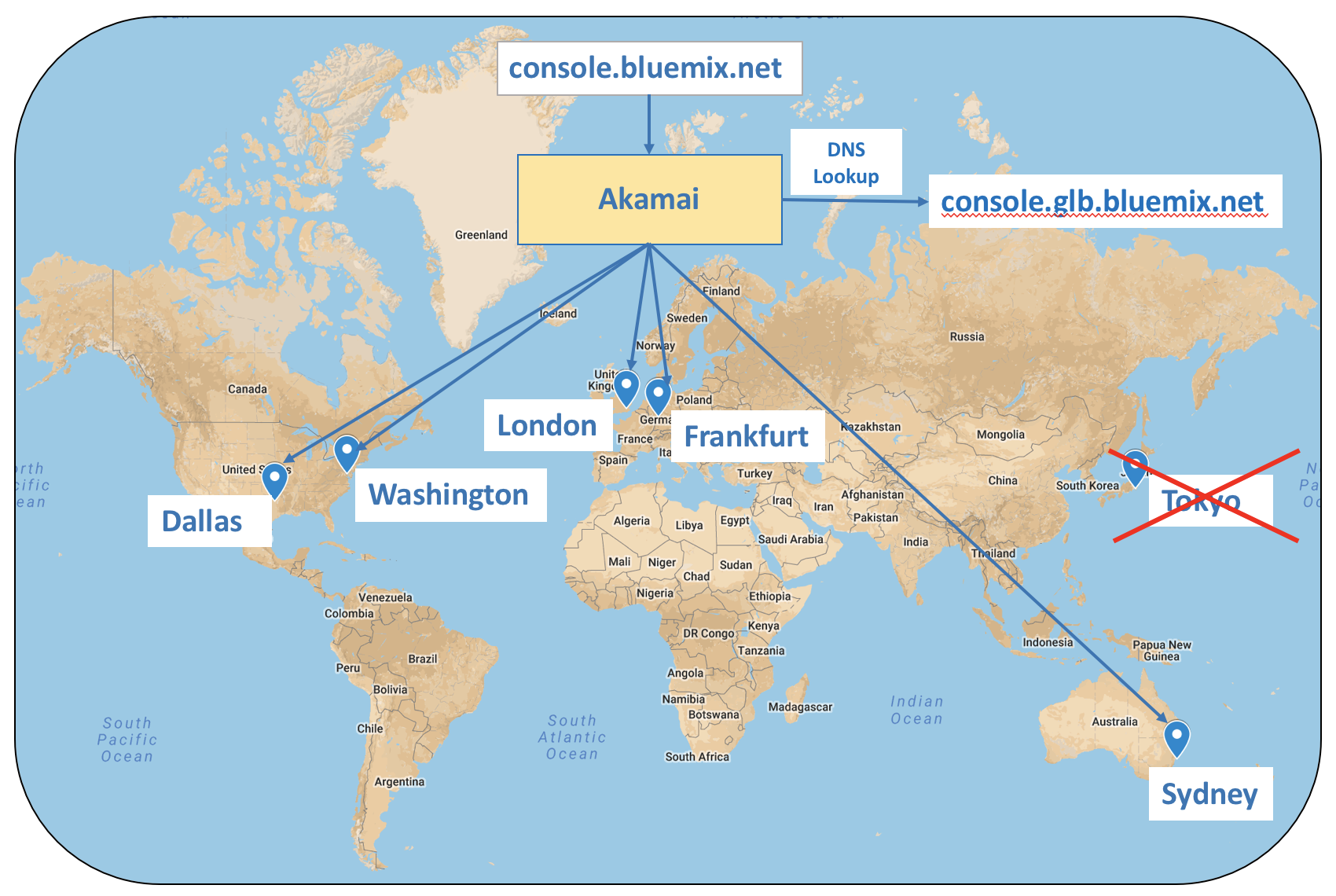

Every 60 seconds or so, Dyn checks the health of each console deployment by probing a health check API written by my team. If the health check cannot be reached or if it responds with a 40x or 50x error, then Dyn marks the associated data center as unhealthy and takes it out of the rotation. This is what is meant by a “failover.” At this point, requests that would go to the unhealthy deployment, are instead sent to the next closest deployment. In this way, the user never knows there was an issue and continues working as if nothing has happened. Eventually, when the health of the failed deployment recovers, Dyn will put it back in the rotation and route traffic to it.

In the diagram below, the Tokyo deployment of the console is unhealthy, and traffic that would normally go there starts flowing to Sydney.

Clearly, the algorithm used by the health check plays a very important role in the overall success of the architecture. So, when building your own health checks, you should think carefully about the key components that influence the health of your deployments. For example, Redis is one of our absolutely critical components because we use it to store session state. Without Redis, we cannot maintain things like a user’s auth token. So, if one of our deployments can no longer connect to its local Redis, then we need to failover.

On the flip side, there may be other dependencies that are not nearly as critical. For example, if our Dallas console deployment cannot connect to the API for Cloud Foundry (CF) in Dallas, the majority of the console functionality will continue to work. Other console deployments probably can’t connect to the API either, so there is probably not much point in failing over.

Finally, the health check can be very helpful for making proactive failovers easy. For example, we made our health check configurable so we can force it to return an error code. We have made use of this on several occasions such as when we knew reboots were required while patches for Meltdown and Spectre were being deployed in SoftLayer. We elected to take console deployments in those data centers out of the rotation until we knew those data centers (and our deployments within them) were back online.

Impact to Microservice Implementation

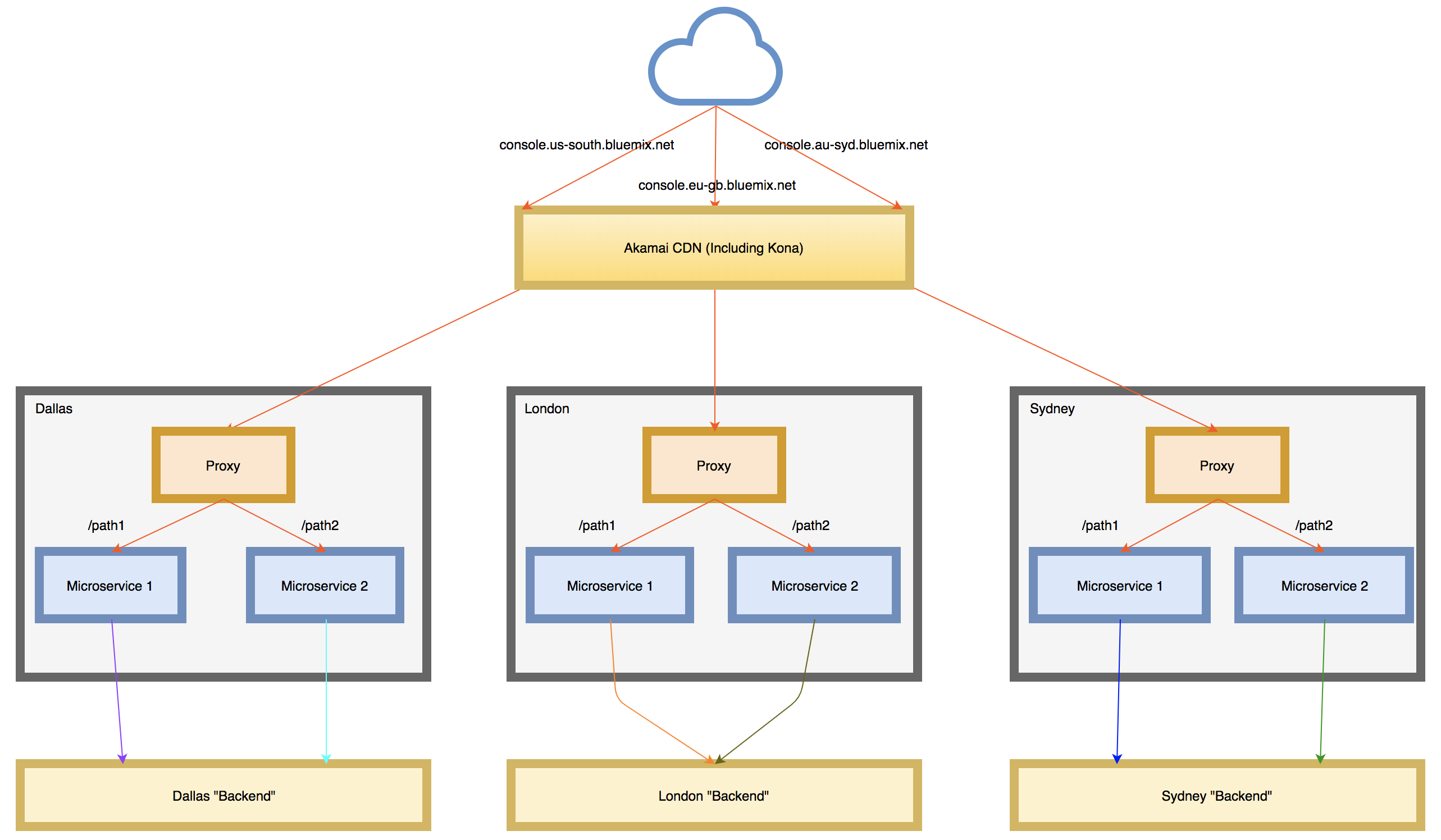

As described in a previous post, each console deployment contains a set of roughly 40 microservices running behind a reverse proxy. In our original implementation, our microservices tended to be tied to APIs in the region they were deployed to. For example, our Dallas deployment could only manage CF resources in Dallas, our London deployment only CF resources in London, and so on. This is illustrated in the pre-Dyn diagram below where microservices in the three data centers only talk to the “backend” within the same region.

This worked fine for us when we had a separate URL for each console deployment and users knew they had to go to the London console URL to manage their London resources. However, this architecture was not conducive to the goals of global console where we wanted the UI to be served from the geographically nearest data center and for it to continue to be accessible even if all but one deployment failed. In order to accomplish this, we needed to decouple the microservices from any one specific region and enable them to communicate with equivalent APIs in any of the other regions based on what the user was requesting. This is shown in the diagram below.

Of course, an astute reader might point out we’d be even better off if all of the backend APIs provided their own globally load balanced endpoints. Then a console microservice would be able to always point at the same host names no matter where deployed. And, indeed, we do have many APIs in the IBM Cloud ecosystem that are moving in that direction.

Smoothing Migration from Cloud Foundry to Kubernetes

This architectural update has been great for us in many ways, and has given us much more flexibility in determining where to deploy the console throughout the world. It has also had the added benefit of making it easy for us to roll-out deployments running on different technologies without end users ever knowing.

Historically, the console has run on Cloud Foundry on the IBM Cloud, but we are nearly done with a migration to Kubernetes (managed by the IBM Cloud Container Service). We have been able to add Kubernetes deployments into the rotation simply by updating our Dyn configuration. This has allowed us to vette Kubernetes fully before turning off our CF deployments entirely. This is represented in the diagram below showing Dyn load balancing between two CF deployments and three Kubernetes deployments.

Conclusion

We’re excited by the improvements in performance and reliability we’ve been able to provide our customers with the global console. I hope some of the lessons and insights that my team has gained in the process will help your efforts as well.

Related Resources

For additional material on this subject, please see Configure and run a multiregion Bluemix application with IBM Cloudant and Dyn by colleague Lee Surprenant.